In Pakistan, healthcare disparities continue to widen the gap between privileged and marginalized populations. Among the most overlooked groups is the transgender community, often referred to as khawaja sira. This community faces unique challenges due to systemic discrimination, poverty, and lack of awareness. One of the most pressing health issues they face is tuberculosis (TB), a disease that thrives in overcrowded, unsanitary conditions—conditions that many transgender individuals in urban areas like Rawalpindi find themselves in. According to public health data, Pakistan ranks among the top ten countries in terms of TB burden, with transgender individuals falling through the cracks of national health reporting systems. Rawalpindi, a key metropolitan area adjacent to the capital, has emerged as a testing ground for inclusive healthcare due to its relative infrastructure and active civil society.

A transgender person standing outside the car © UNDP Pakistan/Shuja Hakim

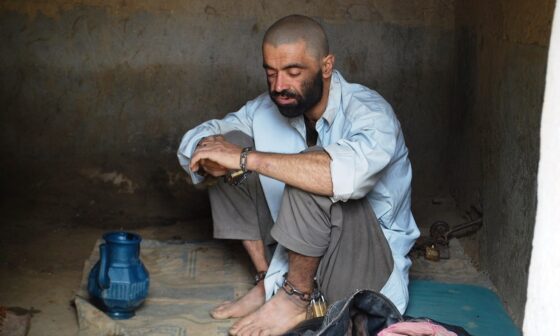

Sana, a 28-year-old transgender woman living in Rawalpindi, offers a glimpse into the hardships of battling TB in an unwelcoming healthcare system. For months, she experienced a persistent cough, night sweats, and fatigue. At first, she thought it was just stress or a minor illness, so she ignored the symptoms. Seeking medical help was not her first instinct; past experiences had taught her that visiting hospitals could be more traumatic than helpful. “They don’t even look us in the eye,” she explained, recalling how medical staff treated her during her last hospital visit. Social stigma, compounded by poor economic conditions, meant that her health took a back seat to daily survival. Many transgender people in similar circumstances resort to community shelters or live in overcrowded housing where TB transmission is more likely, but rarely detected early.

It wasn’t until she heard about a community-led TB screening initiative that she considered getting tested. A peer educator informed her about a mobile van service set up near her neighborhood—an effort by a local NGO in partnership with the National TB Control Program. The service was designed to be non-discriminatory and welcoming to all, especially transgender individuals. Encouraged by friends and the knowledge that others had positive experiences, Sana decided to go. She underwent a chest X-ray and sputum test on-site. When the diagnosis came back—pulmonary tuberculosis—Sana was shocked but relieved. The health workers treated her with dignity and provided medication for free. She was also given regular follow-ups and mental health support. “This was the first time I felt like a human being in a medical setting,” she said.

Her story is not unique but emblematic of a larger shift in how healthcare can be delivered with compassion and inclusivity. These targeted TB initiatives in Rawalpindi are part of a broader strategy to make healthcare accessible to all, regardless of gender identity. The campaign included mobile diagnostic vans, peer-led education sessions, and sensitivity training for medical personnel. Hundreds of transgender individuals were screened, and many began treatment with high adherence rates, thanks to continuous community support and follow-up care. Peer educators played a vital role in bridging the gap between the healthcare system and the transgender community, fostering trust and ensuring better outcomes. By treating transgender patients with respect and confidentiality, these programs broke a historic cycle of neglect.

Breaking Stigmas: How Trans Communities in Pakistan Are Battling Tuberculosis

Despite these successes, challenges remain. Stigma within the healthcare system persists, and there is still no formal national health policy that specifically addresses transgender health needs. Many transgender individuals are still undocumented or excluded from official census data, making it difficult to tailor health services effectively. Funding for such initiatives is limited, and expansion to other cities is constrained by resource shortages. Rawalpindi’s model shows promise but is currently the exception, not the rule. Cultural taboos and political hesitance hinder scalability, though international donors and local organizations continue to push for broader implementation. Without systemic change, such community programs may remain isolated efforts rather than transformative public health models.

Ripples of #coronaAPCOMpassion: Supporting MSM, transgender and LGBTIQ individuals, one country at a time

The experience in Rawalpindi offers a replicable model for other urban centers like Lahore, Karachi, and Peshawar. These cities also have sizable transgender populations and are equally in need of inclusive healthcare interventions. Policymakers must recognize that health equity cannot be achieved until the most marginalized are accounted for in planning, funding, and service delivery. Integrating transgender health into national TB policy frameworks will require multi-stakeholder cooperation involving government, NGOs, healthcare providers, and community representatives. Sana’s journey from silence and suffering to recovery and dignity stands as a testament to what inclusive healthcare can accomplish. Pakistan’s fight against tuberculosis will only succeed if it becomes a fight for the rights and well-being of all its citizens—transgender individuals included. By placing compassion at the heart of healthcare, Rawalpindi has lit a path others can follow.

References:

Journal of Public Health in Developing Countries. (2023). “Peer-Led Models in Tuberculosis Detection and Control.”

National TB Control Program Pakistan. (2023). Annual Report on Tuberculosis Control in Pakistan.

World Health Organization. (2023). Global Tuberculosis Report 2023.

UNDP Pakistan. (2022). Health Inequality in Marginalized Communities.

Transgender Rights Consultants Pakistan. (2022). Inclusive Healthcare Models: A Case for Transgender Health Rights.

Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. (2021). Demographic and Health Survey.

Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. (2023). Discrimination in Healthcare Access Among Transgender Individuals.

Ministry of National Health Services. (2022). TB Screening Projects in Urban Pakistan.