Mental health remains one of the most misunderstood and neglected aspects of healthcare in Pakistan, especially in rural areas where awareness is limited, and traditional beliefs dominate. Anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia affect millions across the country, yet these conditions are often dismissed as weaknesses of character or even attributed to supernatural causes. In villages, where healthcare facilities are scarce and education levels are low, mental illness carries a heavy stigma. Families often hide the suffering of loved ones to avoid community gossip or social exclusion. The lack of proper diagnosis, counseling, and treatment only worsens the conditions, leading many patients to silently endure their pain. Breaking this stigma requires a cultural shift that prioritizes mental well-being as an essential part of overall health.

From Stigma to Support: How Pakistani Media is Changing Mental Health Narratives”

Consider the case of Ayesha Bibi, a 28-year-old mother of two from a remote village in Bahawalpur. After the birth of her second child, Ayesha began showing signs of postpartum depression—persistent sadness, withdrawal, and feelings of hopelessness. Her family, unaware of maternal mental health issues, believed she was under the influence of a spiritual curse. Instead of consulting a doctor, they took her to a faith healer who performed rituals to “remove evil spirits.” Months passed, and Ayesha’s condition deteriorated to the point where she refused to eat or care for her children. It was only when a visiting NGO worker recognized her symptoms and referred her to a psychiatrist in Multan that Ayesha received proper treatment. Her recovery was slow but steady

The deep-rooted stigma surrounding mental health in rural Pakistan is fueled by multiple factors. Cultural norms often equate emotional struggles with weakness, while spiritual explanations are more readily accepted than medical ones. Gender inequality worsens the problem; women are more vulnerable to mental health disorders due to social pressures, domestic violence, and limited autonomy, yet they have fewer avenues for seeking help. Furthermore, there is a dire shortage of trained psychiatrists and psychologists in rural areas. According to health reports, more than 70% of mental health professionals are concentrated in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, leaving rural populations dependent on untrained practitioners. Even when services are available, the cost of treatment and the fear of being labeled “mad” discourage families from seeking help.

How primary health care can bridge the mental health gap | PATH

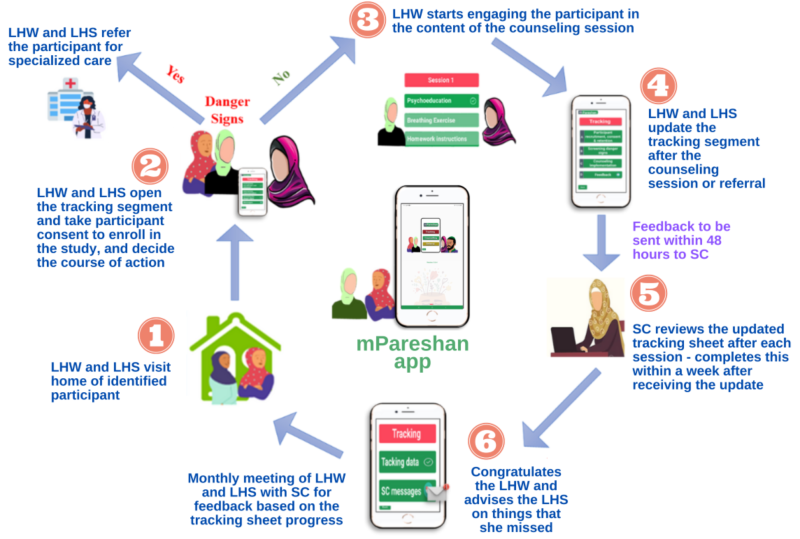

Breaking this cycle requires targeted awareness campaigns that are culturally sensitive and community-driven. Schools, mosques, and local leaders can play a powerful role in changing perceptions by openly discussing mental health and dispelling myths. Training Lady Health Workers (LHWs) to identify and support individuals with mental health issues can make early intervention possible. Additionally, telemedicine platforms are increasingly bridging the gap between urban specialists and rural patients, offering consultations without the need to travel long distances. Community-based support groups can also reduce isolation for those struggling with mental illness, showing them they are not alone. Integrating mental health education into rural primary healthcare services would normalize conversations and reduce stigma over time.

How primary health care can bridge the mental health gap | PATH

The government’s role is equally important in addressing rural mental health challenges. Pakistan’s National Mental Health Policy emphasizes the need for decentralizing mental health services, but implementation remains slow. Allocating funds for rural mental health clinics, subsidizing medications, and incorporating mental health into existing public health programs are critical steps. Collaboration with NGOs and international organizations can strengthen outreach initiatives and provide sustainable solutions. Moreover, media campaigns in regional languages, featuring relatable stories and testimonials, can gradually shift public attitudes toward compassion and understanding. Long-term success will depend on consistent policies and community participation rather than one-time projects.

Community-Based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) Service Delivery in Humanitarian Settings in Rural-High-Risk-Districts of Sindh and Balochistan, Pakistan | MHIN

If mental health stigma in rural Pakistan continues unchallenged, it will silently perpetuate cycles of suffering, poverty, and social exclusion. Ayesha Bibi’s story is a reminder that mental health is not a luxury but a necessity for every individual’s dignity and well-being. By combining awareness, accessible care, and cultural sensitivity, rural communities can begin to see mental illness as a treatable health condition rather than a source of shame. Bridging this gap is not only a medical obligation but a moral one, ensuring that no one suffers in silence due to ignorance or fear. With sustained efforts, Pakistan can build a future where mental health is valued equally alongside physical health, creating healthier and more resilient rural societies.

References

UNICEF Pakistan (2023). “Community Health Workers and Mental Health Education.”

World Health Organization (2023). “Mental Health in Low-Resource Settings: Challenges and Opportunities.”

Pakistan Institute of Mental Health (2022). “National Report on Mental Health Stigma in Rural Areas.”

Journal of Rural Health (2023). “Barriers to Mental Health Services in Developing Countries.”

The Express Tribune (2023). “Breaking Myths: Mental Health Awareness in Punjab’s Villages.”

Dawn News (2022). “Why Rural Women Bear the Brunt of Mental Health Neglect.”

Human Rights Watch (2023). “Gender Inequality and Its Impact on Mental Well-Being.”

Aga Khan University (2022). “Telemedicine as a Tool for Expanding Mental Health Care in Pakistan.”