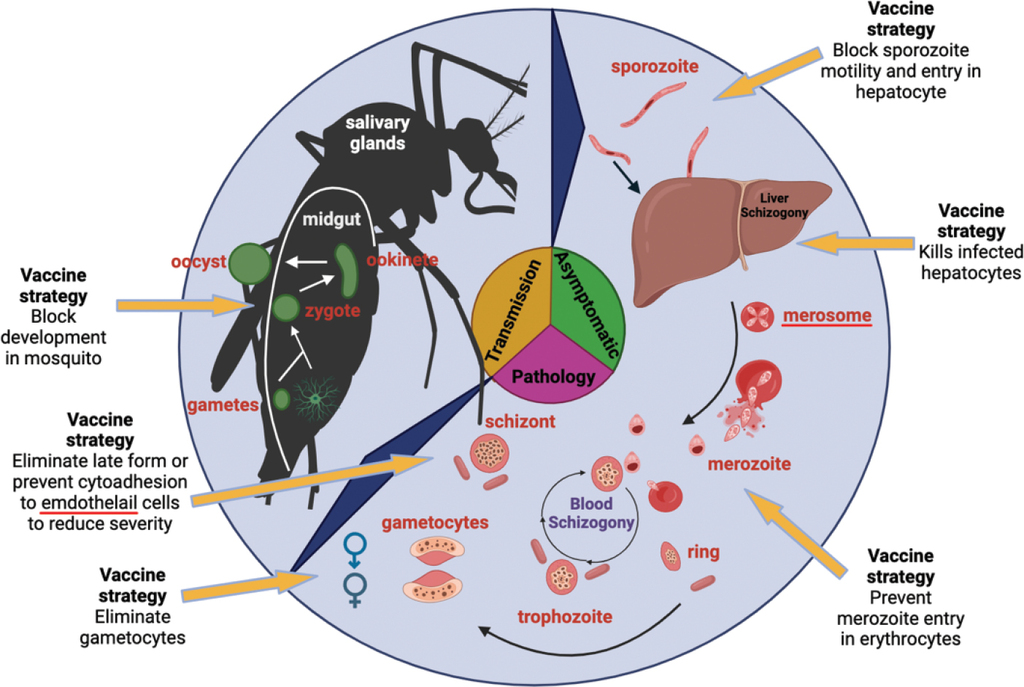

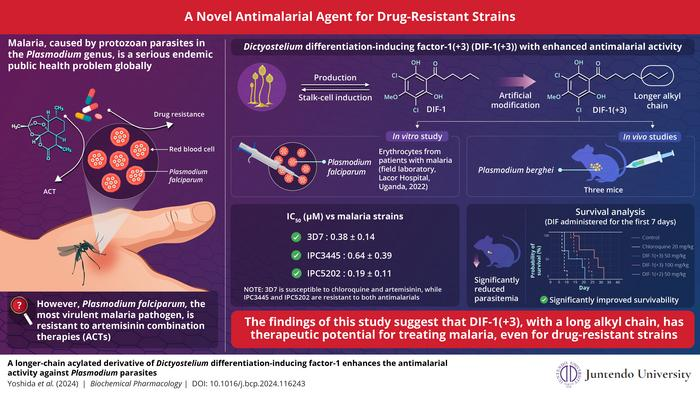

Malaria has long been a persistent public health threat in Pakistan, particularly in rural and flood-prone regions such as Balochistan, Sindh, and parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito and caused by Plasmodium parasites, malaria continues to affect thousands of people every year, with seasonal peaks during and after the monsoon. What’s more alarming is the increasing evidence of drug-resistant malaria strains, which are making treatment more difficult and expensive. These resistant strains are particularly dangerous in rural communities, where access to timely and proper healthcare is already limited. Tackling malaria and preventing drug resistance in such areas requires a multipronged approach involving awareness, early detection, prevention, and proper use of antimalarial medications.

Malaria: past, present, and future | Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy

In the small village of Jhal Magsi in Balochistan, 9-year-old Shabana developed high fever, chills, and vomiting after a flood swept through the region in 2022. Her parents, unaware of the symptoms of malaria, treated her with herbal remedies for two days. When her condition worsened, they traveled over 40 kilometers to the nearest Basic Health Unit, where she was diagnosed with Plasmodium falciparum—a dangerous type of malaria. Unfortunately, the initial medication failed to relieve her symptoms, and she was transferred to a government hospital in Quetta. Doctors suspected resistance to the first-line treatment, attributing it to the unregulated use of counterfeit or outdated antimalarial drugs. Shabana recovered after receiving advanced therapy, but her case is just one of many emerging signs that rural Pakistan is grappling with both malaria and growing drug inefficacy.

Frontiers | Evolution and implementation of One Health to control the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes: A review

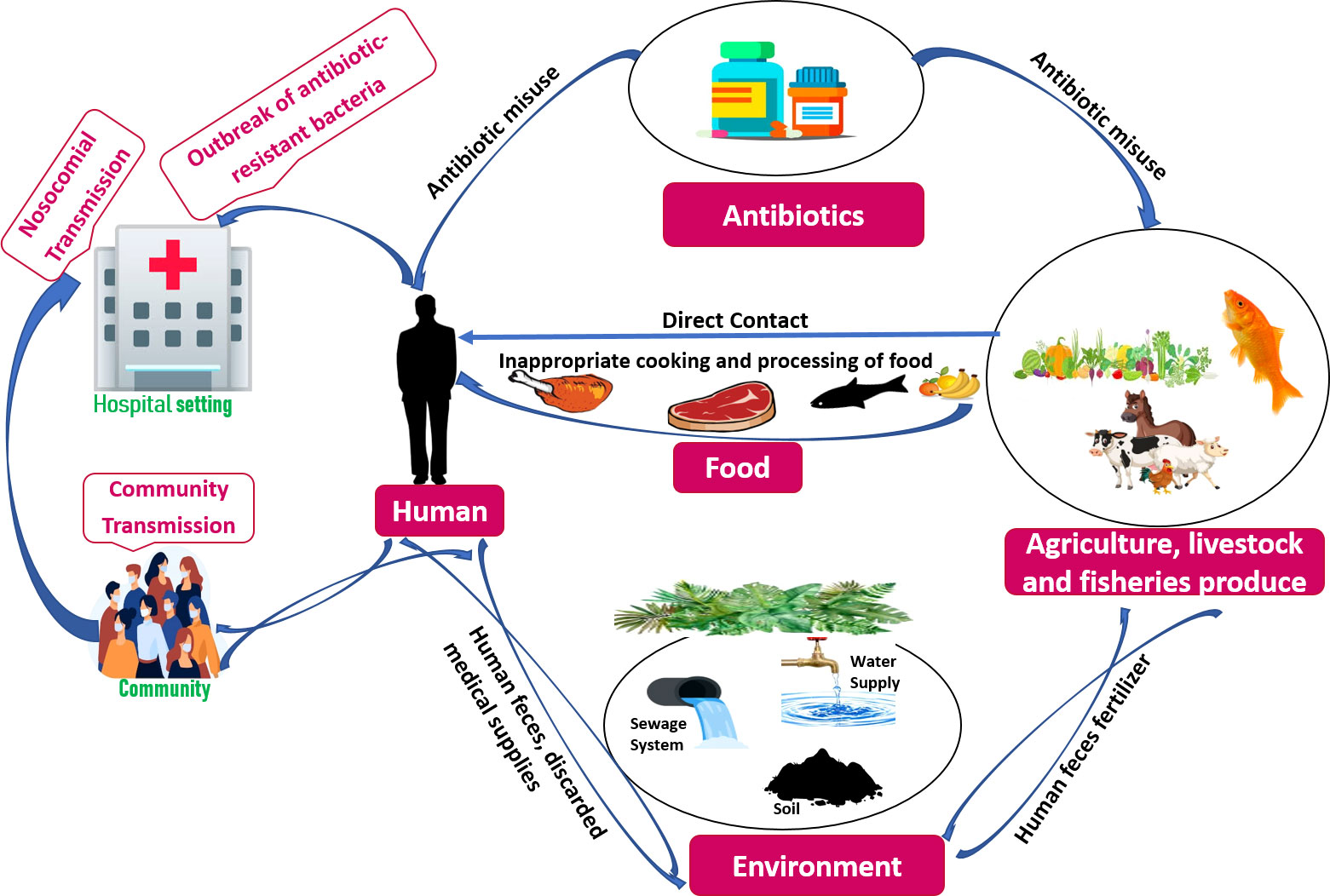

The primary reasons behind drug resistance in malaria include overuse, misuse, and substandard quality of medications. In many rural areas of Pakistan, people rely on unlicensed practitioners or medical stores without prescriptions. Patients often discontinue the full course of medicine once symptoms subside, allowing partially resistant parasites to survive and multiply. Furthermore, some private sellers stock outdated medicines that have lost potency due to poor storage conditions. With no centralized monitoring of drug efficacy in many of these districts, resistant strains are quietly spreading among communities. This puts a strain on local healthcare systems and limits treatment options, especially in high-burden districts like Dadu, Thatta, and Larkana in Sindh, where recurrent floods make malaria endemic.

Malaria | Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, & Prevention | Britannica

Prevention remains the most effective and affordable strategy for controlling malaria in rural communities. Distribution of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs), indoor residual spraying (IRS), proper waste management, and water drainage are all proven methods to reduce mosquito breeding. However, implementation remains inconsistent across Pakistan’s rural landscape due to funding shortages, weak governance, and lack of education. In some parts of Balochistan and interior Sindh, communities still sleep without nets and store water in open containers, unaware that they are breeding sites for Anopheles mosquitoes. Health education campaigns, especially in local languages, need to emphasize the importance of prevention rather than relying solely on treatment after infection occurs

Another critical element is strengthening primary healthcare infrastructure. Rural health centers must be equipped with rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), skilled staff, and a steady supply of effective antimalarial drugs. The training of Lady Health Workers (LHWs) and local volunteers can improve early detection and community reporting. Schools can serve as centers of awareness campaigns, where children are taught basic mosquito control practices and symptom identification. Government-NGO collaborations, like those seen in the Global Fund programs in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, show promise but require sustained funding and political support. Additionally, regulating drug distribution and cracking down on counterfeit medication is essential to preventing the escalation of resistant malaria strains.

Agriculture’s impact on malaria | Working in development

Pakistan’s battle against malaria, especially in its rural heartlands, will define the future of public health resilience in the country. With climate change increasing the frequency of floods, mosquito-borne diseases are set to rise. If drug resistance continues to spread unchecked, the country may find itself dealing with untreatable cases—similar to what parts of Southeast Asia have faced in the past. However, by investing in grassroots awareness, strengthening rural health systems, regulating drug use, and ensuring preventive tools reach the last mile, Pakistan can still reverse this dangerous trend. Shabana’s story is a warning and a reminder: early intervention, proper medication, and community education can save lives where healthcare access is a daily struggle.

References

UNICEF Pakistan (2023). “Community-Level Health Education and Disease Prevention.”

World Health Organization (2023). “World Malaria Report – Global and Regional Burden of Malaria.”

National Institute of Health Pakistan (2022). “Annual Surveillance Report on Malaria in Pakistan.”

Journal of Infectious Diseases in Developing Countries (2023). “Emergence of Drug-Resistant Malaria in Rural Pakistan.”

The Lancet Global Health (2022). “Climate Change, Flooding, and Malaria Risk in South Asia.”

Dawn News (2023). “Health Crisis in Balochistan After Monsoon Floods.”

The Express Tribune (2022). “How Rural Healthcare is Failing to Address Drug Resistance.”

Global Fund for Malaria (2022). “Partnerships for Prevention and Malaria Elimination.”